Re-Valuing, Appropriating, and Valorising Electronic Waste in Tanzania

The planet has entered a period where traces left by humans can be witnessed almost everywhere. Waste is one of the most distinctive marks left by human activities on earth. Waste produced by humans can be found even in the most remote areas – at the bottom of the sea, in arctic regions or deep in tropical forests. Economies and daily lives are connected to waste – its production, sorting, reusing, and recycling, or removal from sight.1

The number and variety of electronic devices in circulation today is as commonplace as it is daunting, with households, workplaces and daily lives dependent on electronic devices. Plug-in toasters and kettles are used to prepare breakfast; offices are organised around computers and printers; cars run on batteries, and meetings are held via conference calls, emails, or short message services. Electronics are viewed as markers of progress, symbolizing human control over time, distance and space. More importantly, they have become an essential part of ourselves, perhaps to the extent that they can be considered as cyborg prostheses.2

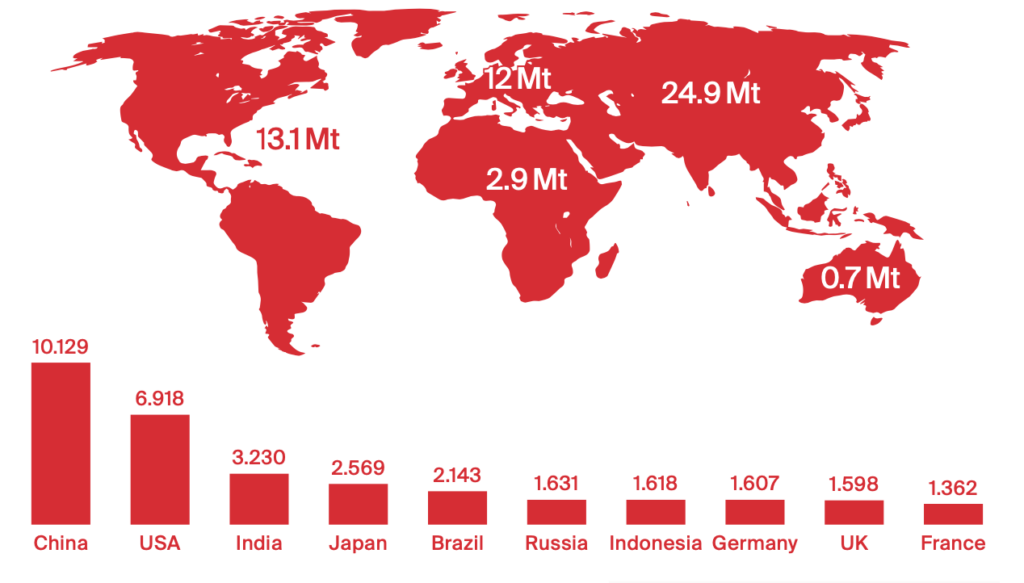

However, these electronics have limited lifespans, and with them, streams of waste are emerging that affect the planet and regions of the world in uneven ways.3 In 2020, 55.5 million Mt of e-waste were produced globally, an increase of 1.9 million Mt from 52.6 million Mt in 2019. This number is expected to reach 74.7 million Mt by 2030.4

Statistics on the biggest global producers of e-waste (Murthy and Ramakrishna 2022).

New electronic technologies and products are constantly being introduced to the market, and people, especially in wealthy countries, are encouraged by unique and better models and marketing strategies to keep switching to new devices and discarding older ones. Consumption is intertwined with the need to constantly acquire new products and increased rates of waste production.5 Consumption has also been accelerated by the availability of a wide variety of goods in the market, to the extent that even moral values, like repairing and taking care of things, are at the margins of consumer considerations.6 These factors have increased consumers’ excitement for acquiring newer gadgets, alienating them from the very products they buy and creating personal ‹ inner impoverishment › or inner hunger.7

Waste collector on the streets of Dar es Salaam.

As more electronics are bought and discarded, they have to go away, BUT not into ‹ our › backyards.8 They must end up somewhere, in the ‹ wastelands ›9 or the domiciles of ‹ wasted lives ›10. In many cases, these places are in the least developed countries. While electronic devices might hold no or low value in the Western world, they emerge in remarkable ways and enter new assemblages of relations in the Global South.

In 2019, the world produced 53.6 million metric tonnes (Mt) of e-waste, a 21 % increase in five years. Seven to 20 % of the amount produced in 2019 is estimated to have been exported for second-hand use to developing countries where demand for technologies is higher but purchasing power of the majority is lower in relation to prices of new products.

However, when e-waste arrives in the global south, « informal » recyclers ingeniously, creatively, and innovatively create new value assemblages. Although these informal value-recovering practices are zig-zag conglomerates, they surprisingly provide ‹ coherences, interfaces, and connections › of value-regenerating activities that help people address the challenges of daily life while feeding back into local and global value chains.11 Hence, e-waste becomes more than just ‹ waste › or ‹ disorder ›.12 Instead, e-waste enters and converges into news sociocultural and economic networks. Since these globalised streams of waste are unjust and oppressive, it is insightful to look closely at and study specific examples, as such local dealings may hold solutions to a global problem.

The workshop

In October 2018, seven months after starting my field research in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, I was introduced to a workshop known as Mahakama Ya Friji. The name Mahakama Ya Friji reflects the activities at this place. Most of the informal e-waste recycling activities in Dar es Salaam are conducted on corners and in backyards around the city. I remember my first day at the workshop. From a distance, a building fully covered with corrugated iron sheeting was visible, with piles of scrap materials scattered around it, from which banging noises, loud voices and smoke emanated. Standing a few metres from the entrance to wait for my host George, a charcoal stove artisan and one of the workshop leaders, I saw men sitting on old car seats with pieces of rail between their feet and hammers in their hands. As they hammered away, I could attribute the sounds I had heard metres away while approaching the workshop.

Mahakama Ya Friji is a workplace, where ‹ e-waste is reshaped, one life ends, and a new life starts ›, as George once said. Mahakama Ya Friji is a transient place; materials are ingeniously revalued, repurposed, and reshaped. At the workshop, defunct things acquire new value and functions. The workshop is not a cast-off place; it is not a ‹ Gomorrah ›, as informal waste recycling places in African cities are portrayed by the international media.13 These places are not mere recipients of technology, sites of backwardness in techno-capitalism, or spaces out of place or wastelands. The usual narrative is that these places are separated from their cities, found on empty grounds and apocalyptic sites.

The workshop is also not, or not only, a place of toxic violence. One could view the workshop as a ‹ disposable › place, a place for disposable materials and bodies, showing the savage side of e-waste, the workshop as a place where labour is exerted and commodities produced. A study by Kyessi and Omar (2018) found around 85 workshops in the Kinondoni district, one of four districts that form the Dar es Salaam metropolitan area. Approximately 2,125 people work in these workshops.14 Mahakama ya friji is in the middle of Mwananyamala, a bustling low-income residential area in Kinondoni. At the workshop, there are around 20 scrap collectors – almost all young, in their late teenage years to their 20s – as well as 25 to 30 charcoal-stove crafters and three scrap dealers.

To understand the mushrooming and perseverance of these unregulated e-waste recycling sites, specifically in Tanzania, we need to look at and analyze what has become of e-waste beyond the informal recycling centers. Observing how and in what ways e-waste is recycled does not provide a comprehensive picture of what it becomes. Sticking with e-waste means relentlessly pursuing it until it is scattered to the winds, if it is at all.

It is therefore crucial to observe processes and practices, networks, relations, and assemblages beyond the chopping, dismantling, salvaging, and burning of e-waste. In this article, I intend to track just one aspect of e-waste as it percolates from Mahakama ya friji workshop throughout the broader society in Dar es Salaam. Following and observing materials and activities beyond recycling, allows us to track where these materials go, what they turn into, and what they gather. And why are they essential in incentivising informal recycling?

Welcome to Sodom or welcome to solutions?

Informal waste work has been portrayed as catastrophic, a recreation of Sodom, as depicted in the 2018 documentary ‹ Welcome to Sodom ›, directed by Austrian filmmakers Florian Weigensamer and Christian Krönes.15 However, if we pay attention and learn from informal activities that address the waste problem, we may find the solutions we seek. In the current technological epoch, a tendency exists to believe that only advanced technology provides answers to the problems we face. Meanwhile, micro-scale, ingenious activities developing around those problems are usually overlooked by governments, tech companies and even researchers.

These unrecognised activities, like the ones at Mahakama ya friji, which spontaneously arise out of these unregulated patches, create platforms for a potential un-projected sustainable urbanisation. E-waste is considered a problem in African cities. However, practices around these defunct electronics (i. e., refurbishing, recycling, reusing, and repairing) envisage a future through ingenuity and creativity that gradually creates grounds for economic security. These ‹ micro activities › are valuable in building the city. They are not just compensational for allegedly missing infrastructures. Instead of viewing informal economies as ‹ compensation for the lack of successful urbanisation ›, African cities must be considered complex spaces. They appear to not necessarily follow any particular Western urbanisation models.16

Scrap business at Mahakama Ya Friji. & Samwel and George working on the cookstove.

Formal recycling models proposed by technocrats, replicating Western countries’ models, would fail in Dar es Salaam and many cities in the Global South. Proponents of formalisation of e-waste recycling who argue that formalisation would provide job and social security, pensions and reduce ecological implications, do not understand the situation on the ground, and in this case, in Tanzania.

First, owners of devices know that they can make money from their waste, so they won’t give things away for free or pay for the collection service. And even if recycling companies decide to buy these items, the companies cannot obtain such skills or hire the people who possess such skills. As I have shown above, collectors, crafters, scrap dealers and even the coffee brewer earn more than the country’s minimum formal salary. On top, social security and pension arrangements in Tanzania do not attract workers from the private sector. Social security is built on kinship relations whereby the working generation supports the younger to access education and skills needed. Once the younger join the labour, they are obliged to support the elders.

Second, Informal recycling, as I have shown above, employs thousands of workers. Companies, because of advanced technologies, will not absorb all of them. Hence informal recycling will continue. In the following, I will also show that e-waste supports social-cultural and economic activities. Charcoal stoves made from salvaged materials are the primary cooking stoves in urban Tanzania. As long as charcoal stove demand is high, there will be informal workshops.

Last, in the face of failing crops production in rural areas due to climate change, with horrible and exploitative pricing of crops from the market, and the lack of agricultural inputs since the adoption of the Structural Adjustment Program under the Bretton Woods institutions, governments were forced to cut agricultural subsidies and make the daily lives of farmers in rural areas more difficult. No one cares about Western liberal environmentalism. Livelihood comes in front of the environmental agenda.

Therefore, I argue that formal recycling would not be able to compete against informal structures. The introduction shows that e-waste will continue to be exported to developing countries. And at the same time, the internal production of e-waste is also increasing at a fast pace. Tanzania and many countries in the Global South do not have infrastructures to handle the volume of e-waste and even if they had them, they would definitely end in informal workshops. The answers do not lie in copying and pasting models from somewhere else. We need to pay attention to the practices in these workshops and find the answers there.

The social life of the charcoal stove

It is a regular evening; scrap collectors arrive at Mahakama Ya Friji from their long days in Dar es Salaam’s suburbs, soaked with sweat, tired, dirty, and thirsty. They push their toroli (carts), full of material objects like car parts, refrigerators, monitors, kettles, iron sheets, and many other things collected from people’s homes, offices, and a few from dumping places. Materials brought to the workshop contain the footprints of people’s lives and memories. Once, they were new and adored by their owners; now, they have been carried from backyards and dumpsites to end up at Mahakama Ya Friji.

‹ Hey Sam, let us check for an aluminium sheet to make your coffee friend a nice stove, › George, a crafter, invited me to follow him. During my fieldwork, I developed a habit of drinking coffee at a local coffee shop. It is not a coffee shop like Starbucks as one could think, just a few benches, a table, and a charcoal stove under a neem tree next to a bus stop. On mornings and evenings, the shop is crowded with men holding small cups filled with either thick, dark coffee or sweetened ginger tea.

The old pro-ruling party generation meets here for hot political discussions with younger opposition supporters. Red-and-white Simba sports club fans joke with the yellow-and-green Dar Young Africans supporters. I spent most of my mornings and evenings here, listening and sometimes participating in the discussions. During this time, I connected well with the coffee brewer, for whom I promised to make a double charcoal stove for his business: one side for coffee and the other for ginger tea.

The old pro-ruling party generation meets here for hot political discussions with younger opposition supporters. Red-and-white Simba sports club fans joke with the yellow-and-green Dar Young Africans supporters. I spent most of my mornings and evenings here, listening and sometimes participating in the discussions. During this time, I connected well with the coffee brewer, for whom I promised to make a double charcoal stove for his business: one side for coffee and the other for ginger tea.

George and I walk among the pushcarts, looking for aluminium boards from refrigerators for my coffee stove. I can see George’s fingers, coarse with uncountable hammer injuries, carefully assessing the boards by touching and bending them. The intimate interaction between George and the aluminium reveals the life prints they share. One could see this as an encounter between George and a defunct object, but also as labour in the process of transforming waste into value. He touched one refrigerator and gazes at it before saying, ‹ this one is just perfect ›.

Crafter’s salvage what the collectors have scavenged, either by searching for specific materials they want to use or by looking at the available materials to spark their minds in terms of what they might be turned into. It took George, one of his apprentices and me two hours to produce a double pot charcoal stove which I delivered in the evening to my friend, the coffee brewer.

The coffee place is called kijiwe or kijiweni,17 where people meet, drink, and talk. People of all kinds come here. Several benches surround a wooden table under a neem tree next to Macho bus stop, one of the busiest bus stops on the Msasani Peninsula, the wealthiest part of Dar es Salaam. People working in consulates, businesses, housing, cleaning, and transportation stop here every day before and after work for a cup of coffee or ginger tea.

The brewer usually opens at 5 a. m. He brings his stove and starts the fire. Within half an hour, the place gets crowded. First to come are the bus drivers and conductors, who usually wake up at 4 a. m. to start their day. In the evening, the place closes after midnight as people go to bed, and many buses stop shuttling.

The brewer, nicknamed Jiongeze,18 is from the Dodoma region and is famous in Msasani. Jiongeze likes to tell stories but also instigate conversations w hen people are not talking. It is a business strategy. The more people are in intense discussion, the more coffee they drink. While making coffee or cleaning cups, he always reminds those sitting around about what happened some days ago or what he has heard on the news. The discussions start from there. Sometimes, conversations go on for a whole day if the topic attracts enough people. One might leave, go to work, and come back to find a completely new batch of people still talking about the same issue.

Jiongeze sells around 50 around 50 litres of coffee. One cup of coffee, which is 1 decilitre, costs 50 TZS, and a 2.5-decilitre cup of ginger is also 50 TZS. The materials – charcoal, coffee, and water – cost around 6000 TZS (3 USD). So, in a day, Jiongeze makes about 25 000 TZS (11 USD) from coffee a nd 6000 TZS (3 USD) from ginger tea. Ginger tea covers his daily expenses, while the coffee earns the profit. Roughly, based on this daily profit, his monthly income will be around 750 000 TZS (325 USD), more than the monthly salary of a lower-level public servant. The capital to start the kijiwe can be described as follows: one charcoal stove (the cost depends on the type; the one I built with George for him with double pots cost around 40 000 TZS (17 USD); benches and tables made from recycled construction wood (I estimate that these would cost 20 000 TZS (7 USD) for four benches and a table); and cups (these cost 10 000 TZS (4 USD) per set; Jiongeze had around two sets of both coffee and ginger cups).

Coffee places are part of the lively cultural fabrics supported by the charcoal stove made of aluminium from e-waste. It’s important to note that vijiwe are not permanent places – brewers open early in the morning and close late at night, meaning they must carry all their utensils. The charcoal stoves, with their mobility and wind-tolerant features, are the only stoves that can be used in these places. Charcoal cookstoves are entangled with and simultaneously enhance the city’s sociocultural activities. In this way, e-waste becomes more than just a digital afterlife. It is essential and integral to passionate encounters and material value. Cookstoves are part of the broader fabric of the city, cultural performances, and environmental discussions – all of which are connected to the activities at the Mahakama Ya Friji workshop and e-waste.

The charcoal stove is an important object in the city. It assembles socialities at home, outside, and even at workplaces. It admits gender relations and a gendered division of labour, but also allows masculinity (good and toxic) to flourish, while managing to accomodate as well as challenge certain normative values. The cookstove is essential in politicisation and political encounters. Its importance during elections, too, makes vijiwe important spaces for the status quo to consolidate power and for local politics to happen. Jiongeze’s kijiwe, which is located on the border between wealthy and poor neighbourhoods, attracts customers from both sides. Even though there are fancy coffee shops on the peninsula, wealthy and powerful people still come to drink coffee at the kijiwe.

I have presented just one pieces of evidence to show the immense importance of charcoal cookstoves in forming socialities; I have also explored its varied assemblages, and their considerable influence on the economy, politics and socialities. However, alongside its agency, the cookstove is connected to the old refrigerator that George and I dismantled in order to produce it. From this encounter and many others I observed during my research, I argue for the importance of exploring these encounters without ignoring toxicity embedded in e-waste. This might offer answers to some, if not many, of the questions we are trying answer.

| 1 | O’Neill, Kate: Waste, 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Haraway, Donna: «A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century,» in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 1991. |

| 3 | Reno, Joshua: Waste away: working and living with a North American landfill, 2016. |

| 4 | Murthy, Venkatesha; Ramakrishna, Seeram: A Review on Global E-Waste Management: Urban Mining towards a Sustainable Future and Circular Economy, in: Sustainability 14 (2), 01.2022, S. 647; Statista: Global e-waste generation outlook 2030, Statista, 2021. |

| 5 | Ntapanta, Samwel Moses: ‹Lifescaping› toxicants: Locating and living with e-waste in Tanzania, in: Anthropology Today 37 (4), 2021, S. 7–10. Online: ‹https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8322.12663›. |

| 6 | Dumont, Louis: On Value: The Radcliffe- Brown Lecture in Social Anthropology, 1980, in: HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 3 (1), 03.2013, S. 287–315. Online: ‹https://doi.org/ 10.14318/hau3.1.028›. |

| 7 | Bauman, Zygmunt: Wasted Lives: Moder- nity and Its Outcasts, 2013; Miller, Daniel: Normativity and Materiality: A View from Digital Anthropology – Heather Horst, Daniel Miller, 2012, ‹https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1329878X1214500112›, Stand: 17.04.2020; Reno, Joshua: Your Trash Is Someone’s Treasure: The Politics of Value at a Michigan Landfill, in: Journal of Material Culture 14 (1), 01.03.2009, S.29–46. |

| 8 | Doherty, Jacob: Waste Worlds: Inhabiting Kampala’s Infrastructures of Disposability, Bd. 6, 2021. |

| 9 | Chalfin, Brenda: Waste work and the dialectics of precarity in urban Ghana: durable bodies and disposable things, in: Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute 89 (3), 30.07.2019, S.499–520. |

| 10 | Bauman: Wasted Lives, 2013. |

| 11 | Mavhunga, Clapperton Chakanetsa (Hg.): What Do Science, Technology, and Innova- tion Mean from Africa, 2017. |

| 12 | Douglas, Mary: Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, 2003. |

| 13 | Adjei, Asare: Life in Sodom and Gomorrah: the world’s largest digital dump via @gdn-globaldevpro, the Guardian, 29.04.2014. |

| 14 | Kyessi, Alphonce G.; Omar, Hussein M.: Socio-Economic Impact of Scrap Metal Business in Dar es Salaam. The Case of Kinondoni Municipality, in: Researchjournali’s Journal of Economics Vol. 6 (No. 4), 2018. |

| 15 | Adjei: Life in Sodom and Gomorrah, 2014; Weigensamer, F.; Krönes, C (Reg.): Watch Welcome To Sodom, Documentary, 1:36, Blackbox FilmGreenpeaceLand Steiermark, department 9 – Culture, Europe, Ext. Relations, 2018. Online: ‹https://vimeo.com/ondemand/wel cometosodom›, Stand: 01.03.2022. |

| 16 | Simone, AbdouMaliq: People as infrastructure: Intersecting fragments in Johannesburg, in: Public culture 16 (3), 2004, S. 407–429. |

| 17 | Kijiweni is singular and vijiweni plural. The terms describe places where people, mainly men, spend their day discussing issues, drinking coffee, and playing games. |

| 18 | Colloquial Swahili for being innovative. |